Transparencies

As both a material condition and a metaphorical concept, transparency relies on an interplay between the subject and object, the viewer and the viewed. Here, the artists use intensities of material and narrative, tracing

incidences of light, shadow, and time to contend with the complex dynamics of seeing. Situated in the museum’s outdoor spaces, individual acts of viewing become collectively shared encounters. Moments of private visual appreciation intersect with public experience, expanding the relationship between objects and their meanings and questioning the values of intention and truth.

Moving from shadow to light, alongside water, and under falling light, we are guided through various aspects of materiality and perception, encountering urbanism, contemporary celestial geometries, and obscured histories.

Materials like glass illuminate intangible phenomena such as light and memory, portraying their manifestations and effects. Others give tangible form to suppressed and disappearing stories, representing the realities elided in the pursuit of development goals or financial abstractions. Questioning our capacity to see and our tendency to disregard, the works attune viewers to non-human temporalities and ecologies.

Spanning primordial origins, rewritten human histories, and apocalyptic futures, these works focus attention on what is often neglected in humanity’s myopia.

The artists’ layered engagements with transparency invite us to look beyond immediately apparent, instantaneous, or superficial readings, engaging in more complex choreographies of seeing and being seen.

THE ARTISTS:

NABLA YAHYA

SoftBank, 2023

Comprised of three components, SoftBank (2023) interrogates the obscure and obfuscated histories pertaining to the initial construction of the Suez Canal (1859-1869). At the heart of the installation is an occidentalised healing bowl engraved, not with palliative Quranic passages hoping to alleviate the suffering of both mind and body, but with the ideologies of the Saint-Simonian, hyper-capitalistic imperialists masquerading as benevolent public servants, who spearheaded parasitic projects within occupied territories.

The installation speaks to the ways in which cultural hegemony remains a form of capitalist, and moreover, imperialist realpolitik. In 1858, the Suez Canal Company was founded upon the European business practice of

concession: a contract whereby a state grants the management of a public service to a private company. This allowed for the expansion of imperialist exploitation within colonized areas, under the guise of enterprise, thus

appearing to be removed from active colonization. The success of these companies would come at a great loss to their host territory.

In 1854, Ferdinand de Lesseps obtained a concession from the Khedive of Egypt to establish the Company that would go on to construct the canal and maintain operating rights for 99 years. The canal was to become synonymous with the most fiendish tenets of imperialism as the Company

implemented the corvée system of forced labor. Of the 1.5 million indentured workers, thousands died as a result of the grueling circumstances – with much of the dredging being done by hand. Epidemics of cholera took many lives, as the living and working conditions were precarious and unsanitary.

SoftBank focuses on these neglected details, details also disregarded at the Exposition Universelle of 1867. The suffering of workers was made inconsequential. Instead, on display were engineering marvels; machines that had been invented to help workers dredge the canal towards the end of its construction invented by Alphonse Couvreux. Indeed, the “civilizing” proselytizers exhibited their ruthless cruelty – their profits did nothing to secure them from ethical bankruptcy.

SARAH BRAHIM

Flesh Memory 2023

Flesh Memory encapsulates breath, a profound yet unseen motion that connects all life across time; as you read, yours links to the first ever taken. This ceaseless lineage is passed down through generations from grandmother to mother to child. For Sarah Brahim, breath translated into bodily experience is “flesh memory” – all of our conscious and unconscious experiences received through genetics, osmosis, or the environment. Ephemeral without defined form or color “flesh memory” is made of the images within us, the substance of our being, like the transmissions of breath. Inseparable from existence, it is the rhythms, vibrations, and flows of life. The ‘flesh’ emerges not from the external but as an “intrabody” the term used in the phenomenological writing of José Ortega y Gasset to express the subjective interior realm of primal sensation and kinetic experience. An inner life that shapes our embodiment, the intrabody is the reality of our composition, the form we perceive of ourselves from the inside.

The work is fabricated from a biomaterial of algae, underscoring breath’s universal origins. Algae’s photosynthesis, which produces 70% of atmospheric oxygen, enables life on land, linking biological and

atmospheric processes. In this way, the organism channels the living memory that makes all life’s activities possible. The material can become a part of the earth again when its life as an artwork is complete.

Suspended over the courtyard pool, Flesh Memory is inseparable from the setting, its atmosphere of light, wind, water, and reflections, built of movement, sensation, and impressions. The simple act of breath blurs boundaries with the viewer, invoking primal connections to our integration with the flows that sustain all existence.

SAWSAN AL BAHAR and BAHAR AL BAHAR

Waterdust 2023

Under the dome, light descends, falling on the tiles around the Damascene fountain. Sunlight animates the courtyard, stirring time and imagination.

Waterdust is a collection of glass sculptures that trace the patterning and movement of light through the dome. The glass forms intensify the light, highlighting the skilled hands that cut and polished every colored tile, evoking the water that flows from the fountain.

The handblown glass sculptures have been made by craftspeople in Bab Shargi, Damascus, and Berlin, where the craft has been carried.

The work responds to the fountain as an object in the museum’s collection, and to Damascus as its origin. The artists connect to their heritage while shedding light on the dying craft of glassblowing in their city, a craft that first emerged in Syria in the 1st century BCE, but which has suffered greatly over the past decade. Today, the Al Hallak family are the last glassblowers that remain in old Damascus.

Through a rigorous process of tracing, mapping, research, and prototyping, the artists worked with glassmakers in both cities to create the sculptures, linking ancient craft and contemporary art, connecting hands and breaths that create together, echoing the hands that once made the fountain. The work is a dialogue between hands and craft; a dialogue from and about Damascus. The sculptures also reveal the impact of the severe economic situation on the day-to-day process of glassmaking in the ancient city. The lack of fuel for the furnace now means production is limited to one color a month, and a size only the smallest of furnaces accommodates.

Water dust dances with the sun, transforming light between glass, water, and human hands across centuries. Created where sunlight hits the ground, they trace time.

ZAHRAH AL GHAMDI

Anthropocene’s Toll: A Planet Asphyxiated, 2023 Zahrah Al Ghamdi’s installation thoughtfully prompts introspection and advocates for an urgent rethinking of our relationship with the natural world. Enclosed within tight confines, this claustrophobic gathering mutely expresses the precarious state of our planet. Twisted tree limbs, plastic waste, bones, and debris are wrapped and cramped together.

The swaddled tree forms are sentinels of the Earth’s struggle, choked by the suffocating impact of human-induced environmental degradation. Anthropocene’s Toll: A Planet Asphyxiated is a stark metaphor for the planet’s desperate plea for help. The tangled branches frozen in disarray represent the helpless distress of the planet.

By combining natural and man-made elements, Al Ghamdi stages a visceral diorama of environmental exploitation.

The dangers of collective inaction are laid bare, and the work is a sobering reminder of our essential duty to counter climate change and protect our shared home for future generations.

The earth requires stewardship; Anthropocene’s Toll: A Planet Asphyxiated is a clarion call for unified efforts to safeguard habitats and shape a sustainable future.

FARAH BEHBEHANI

Hiya (She) 2023

Hiya (She) is an homage to the 10th-century Syrian Muslim astronomer, Mariam Al-Jliya (also known as Mariam Al Astrulabi), who changed the face of astronomy by pioneering the astrolabe – an early scientific instrument used to measure time and to calculate the position of celestial bodies. In addition to being known for fabricating/ creating the most intricate astrolabes of her generation, Mariam’s work helped develop the fields of navigation and timekeeping, which are central to Islamic rituals.

The form of the installation takes inspiration from the Tughrul tower, a 12th-century brick tomb built for the Seljuk ruler Tughrul in Rey, Iran. Designed as a 24-sided polygon, known as ‘icositetragram’, the shape also functions as an indicator of time, its geometry acting like the hands of a clock creating shadows that change in direction and length depending on the sun’s position. The original brick structure is recreated in colored glass, referencing the tradition of stained glass used in sacred monuments dating back to the Umayyad dynasty. Traditionally created with intricate patterns, they evoke a sense of ethereality and depth, flooding spaces with vibrant colors that are never static. The colors of the 48-paneled glass structure are based on the visible light spectrum, which varies in wavelength across the day. As light permeates the colored glass, it transforms throughout the day, painting its surroundings with a rich interplay of color and light.

HASHEL AL LAMKI

Faraminifera 2023

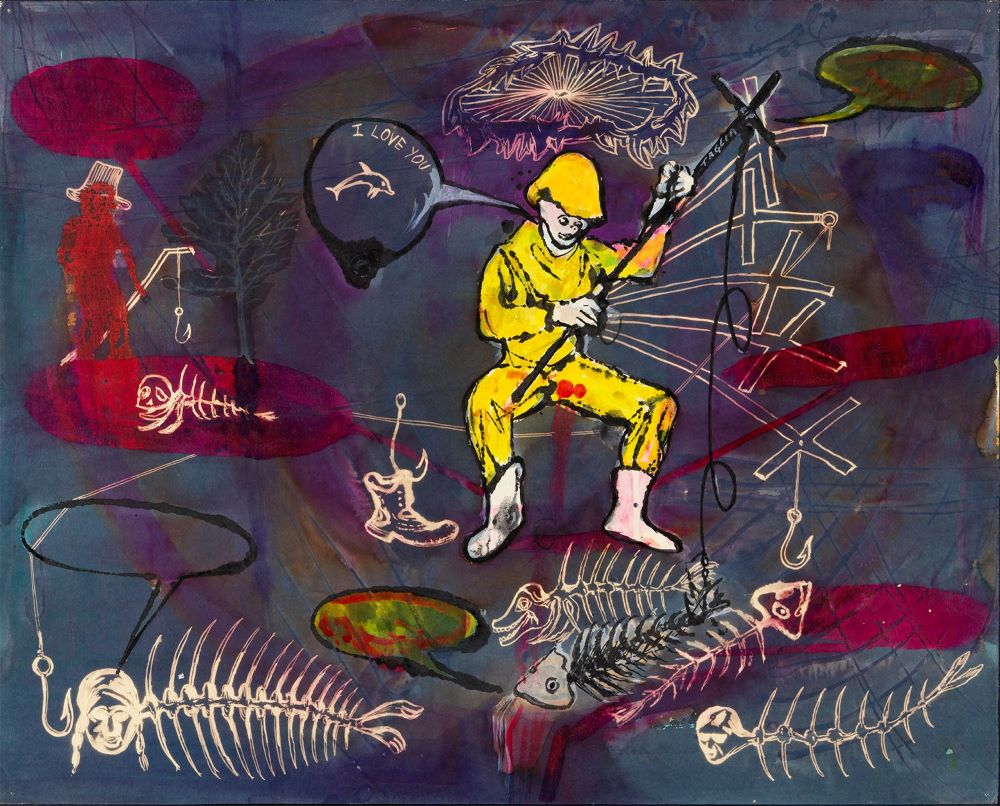

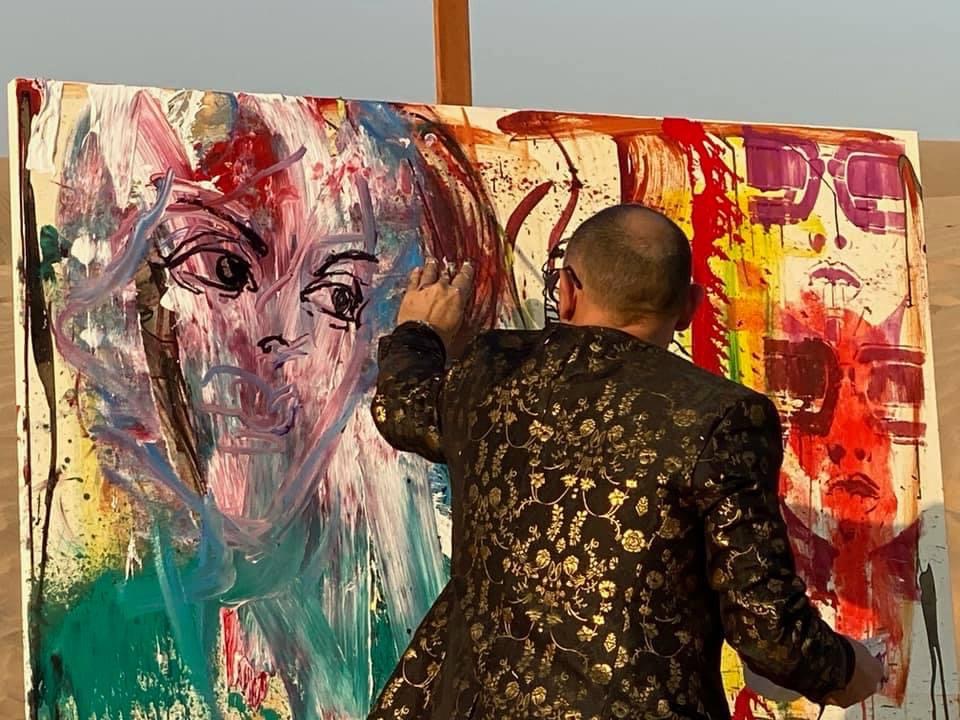

Foraminifera explores the material and cultural significance of pigments, opening questions about modes of perception and comprehension, the answers differing for the painter and the observer. Hashel Al Lamki uses a

painter’s expertise to investigate how different surfaces interact with natural pigments, creating an in-situ mediation that connects us to the past. Using painting techniques that revive the nuances of these ancient

materials, the work reinterprets these histories for today. Within the context of the Louvre Abu Dhabi’s expansive presentation, where works that span time and space bring together disparate civilizations, beliefs, and eras, the work elides generations of artistic encounters in a form that can be experienced either atmospherically or with attention to the material and technical semantics. The work is one, but the encounters vary. The artist’s specialist knowledge of color and material behavior poses questions of legibility and the varied degrees of perception prompted by the same work. As foraminifera

fossils carry historical information, natural pigments symbolize a tangible link to tradition. Traversing the passageway, the public engages with latent information held within the pigments and the process. Meanwhile, the

artist ponders his role: mediating an encounter with the pigments, he cannot directly impart such technical knowledge without becoming didactic. Though the different degrees of knowledge suggests a certain opacity of comprehension, the materiality of these ancient pigments possess a unique transparency that allows light to interact in intricate ways, engaging the space’s play of light and shadow.

ALAA TARABZOUNI

Remember to Forget 2023

This triptych of monochromatic stained-glass panels depicts a singular image – the streets and boundaries of the artist’s neighborhood and a place on the precipice of redevelopment. Unlike traditional stained glass, the

differently-treated panes introduce subtle variations in texture and opacity to create a monochromatic image.

Riyadh’s rapid growth since the 1950s overtook conventional planning methods: large developments ran in parallel, independently shaping the city’s characteristics. Through extensive expansion, many districts can be

defined by micro-localised attributes; the distinctive character of the artist’s neighbourhood was defined by its boundaries; a natural valley to its West and a manmade highway to its East.

These boundaries limited the neighborhood’s urban sprawl, forming a microcosm of the larger Riyadh. Now, with planned redevelopment, it will soon be reconfigured completely.

As memory is challenged and redrawn, the residents’ relation to the place also alters. By imprinting its precarious cartography, its streets, and nuances, in stained glass, the artist pays homage to its current state and documents the instance that she associates with home.

Remember to Forget continues Tarabouni’s examination of boundaries and their physical manifestations, considering their possible typologies – such as natural and constructed, visible and invisible, physical, and

psychological.

The delicacy of the glass suggests ephemeral glimpses of a neighborhood – the intimate streets and rhythms of life within a particular area. The work rediscovers the flows and forms that create a community, while the

transparency of glass reveals rarely contemplated connections: how natural and artificial edges shape our experience, making tangible the elusive boundaries that give meaning to a place.

Louvre Abu Dhabi The first universal museum in the Arab World, translating and fostering the spirit of openness between cultures. As one of the premier cultural institutions in the heart of the Saadiyat Cultural District on Saadiyat Island, this art lovers’ dream displays works of historical, cultural and sociological significance from ancient times to the contemporary era.

From the moment this iconic museum opened its doors in Abu Dhabi, the Abu Dhabi art scene elevated to a global scale, implanting a strong sense of pride in locals and residents alike.