Text by Vittoria Matarrese

At the heart of this exhibition lies the notion of “intrabody,” a term Brahim uses to delve into the intricate connections between our inner selves and the boundless universe. Drawing from her dance background, she orchestrates an intimate dance between her essence and her art, creating a mesmerizing dialogue between her being and her creations. The exhibition spans two floors at Villa Heleneum, resembling a dance studio, featuring video and sound installations, photographs, and sculptures. These elements come together to form a narrative that challenges our understanding of existence and our physical presence in the world.

In his Ethics (1677), Spinoza argued that the spirit cannot destroy itself with the body, and that by knowing this, “we know by experience that we are eternal.” Three hundred years later, French philosopher Alain Badiou added the word “sometimes” to this proposal: “sometimes, we are eternal.” With this adverb, he situated eternity in time. “Sometimes” suggests a sensation, a moment, and a new relationship between the finite and infinite, between universal truths and specific bodies. Eternity could then be defined as a form of infinity in a finite world: the possibility of being brought to a standstill within ourselves, in the inner experience of our own infinity.

In Sometimes we are eternal, Brahim sets out to retrace the past ten years of her life, looking back across the temporal distance that separates this project from an event that changed its course: the tragic loss of a loved one. By “making a stop in time that is also the construction of a new time”, the artist explores the ins and outs of what she calls the “intrabody” and of the surrounding universe. Trained as a dancer, Brahim gives her artworks the appearance of a pas de deux, an intimate dialogue between the dancer and her alterities, in which the form of the exchange remains fluid: this “dialogue” is that of her interiority, between a body that transforms itself and another that transmits, one that abandons resistance for acceptance and another that embraces embodiment. Perhaps this is how the suture between the finite and the infinite operates: the artist allows us to observe, perceive, and understand her as she becomes the subject of different forms of this infinity, an immanent trace within human finitude.

But how can we be transformed by our own gestures, in our bodies, by invisible forces, without fixing the contours? Brahim is interested in transformation, in the localization and dislocation of the self through the body, seeking “a constant rebalancing of the relationship between vertigo and precision,” which could be one of the central articulations of her work, in that it does not imply an absolute but places events on a spectrum of entering and leaving a state of consciousness.

The artist is certainly inspired by dancers and thinkers who, in the 1960s and ‘70s, thought of dance as a heightened experience of life, a search for symbiosis of body, consciousness, and environment. Anna Halprin, considered as one of the pioneers of modern dance, developed a practice that included “tasks” to accomplish, simple actions repeated over and over to focus on the body’s perception and sensitivity. As a result, her pieces moved out of the theater, into the streets, into nature, where she also explored, thanks to the minimalist architectures designed by her husband Lawrence, the use of these dance protocols to help people cope with emotional stress. Around the same time, the philosopher and movement practitioner Thomas Hanna published Bodies in Revolt (1970), in which he defines “soma” as the entire living human process, the body perceived from within, concentrating both mental and physiological events into a single process— essentially, the way in which one’s history, thoughts, images, emotions, and sensations come together and are incorporated and manifested in the experiential body.

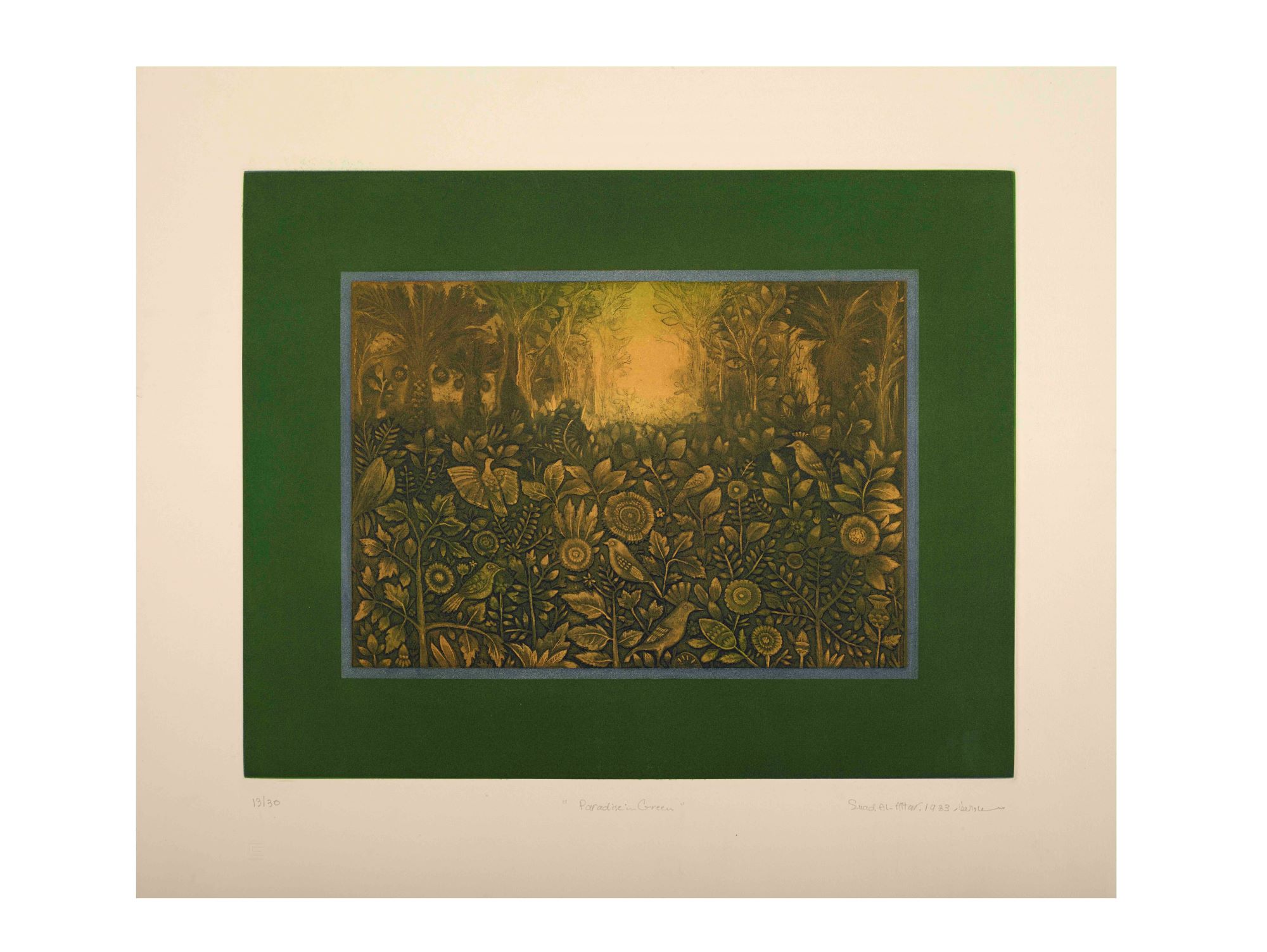

These precedents suggest a possible interpretation of the “tasks” that Brahim explores in her videos and photos: walking, breathing, rising, falling… Simple choreographic texts, to which are added intermediary elements such as light, water, and sound. Body as memory, body as medium, body as reincarnation: our presence in the world, the trace we leave on it transforms the protocol of walking into the score for a landscape. In this way, the ten works in Sometimes we are eternal are each small nuances of a larger theme, in which each work almost speaks of itself. Suspended bodies, breaths, imprints, rhythms, and rituals mingle and follow one another, in installations that extend these back-and-forth movements from the physical body to the “intrabody,” the imperceptible, the spiritual, the distant. The architecture fades away, leaving an expanse as abstract as a dance studio, mental, resilient and luminous, offering the spectator a sense of spatial uncertainty. By immersing ourselves in this sort of landscape, we come to see it as a resource, without focusing on its material dimension: to contemplate it, to anchor ourselves in it, in order to acknowledge it as a space of experience and dialogue, where an intimate collaboration can take place.

The exhibition is closely connected to the place for which it was conceived, the Villa Heleneum, which was built by a dancer, and in which transparency, the presence of water and uncontaminated landscape, surrounds the works, conceived as a collection of fragments, abandoned memories, portions of objects and gestures, readings and sounds. In her creative process, the artist also often refers to the work of Italian architect Aldo Rossi, for whom the question of the fragment in architecture was crucial, composing her creations with inserts or relics of time, symbols of a certain continuity of form, morsels of pre-existence capable of connecting us with what has gone before.

About Bally

Bally is a Swiss luxury brand established in 1851, with a rich heritage in shoemaking, and a longstanding relationship to architecture, the arts and the environment. Today, the brand offers unique designs across shoes, accessories and ready- to-wear, driven by a dedication to craftsmanship and a contemporary aesthetic. The company is owned by JAB Holding Company, a privately held group focused on long term investments in companies with premium brands, attractive growth and strong cash flow dynamics.

About Sarah Brahim

Sarah Brahim was born in 1992 in Riyadh (Saudi Arabia). She lives and works between Portland, New York (USA), and Milan (Italy). She was trained at the San Francisco Conservatory, the London School of Contemporary Dance, and Oregon Health and Science University. Sarah Brahim’s work has been presented at the Islamic Biennale (2023), the Biennale de Lyon (2022), the Diriyah Biennale (2022), and the Noor Festival Contemporary Light Art (2022). In 2023, she was in residence at Robert Wilson’s Watermill Center in New York and received the Baroness Nina von Maltzahn Fellowship for the Performing Arts. She is nominated for the Richard Mille Art Prize 2023 and will be exhibiting at the Louvre Abu Dhabi November-February 2024.

For more information, please visit Bally.com.